When Scientists Develop Products From Personal Medical Data, Who Gets To Profit? | Artificial intelligence

Katherine Streeter for NPR

Katherine Streeter for NPR

If you go to the hospital for medical treatment and scientists there decide to use your medical information to create a commercial product, are you owed anything as part of the bargain?

That’s one of the questions that is emerging as researchers and product developers eagerly delve into digital data such as CT scans and electronic medical records, making artificial-intelligence products that are helping doctors to manage information and even to help them diagnose disease.

This issue cropped up in 2016, when Google DeepMind decided to test an app that measures kidney health by gathering 1.6 million records from patients at the Royal Free Hospital in London. The British authorities found this broke patient privacy laws in the United Kingdom. (Update on June 1 at 9:30 a.m. ET: DeepMind says it was able to deploy its app despite the violation.)

But the rules are different in the United States. The most notable cases have involved living tissue, but the legal arguments apply to medical data as well. One of the best examples dates back to 1976, when John Moore went to UCLA to be treated for hairy cell leukemia.

Prof. Leslie Wolf, director of the Center for Health, Law and Society at the Georgia State University College of Law, says Moore’s doctors gave him good medical care, “but they also discovered there was something interesting about his cells and created a cell line from his cells without his knowledge,” she says.

“And what complicated things even more is they asked Mr. Moore to travel down from his home in Seattle to L.A. multiple times, for seven years, to get additional cells without telling him they had this commercial interest in his cells.”

Moore sued. In 1990, The California Supreme Court decided that he did not own his cells, but found his doctors had an obligation to inform him that his tissue was being used for commercial purposes and to give him a chance to object. Moore reached a settlement following his court battle, “but Mr. Moore certainly felt betrayed through the process,” Wolf says.

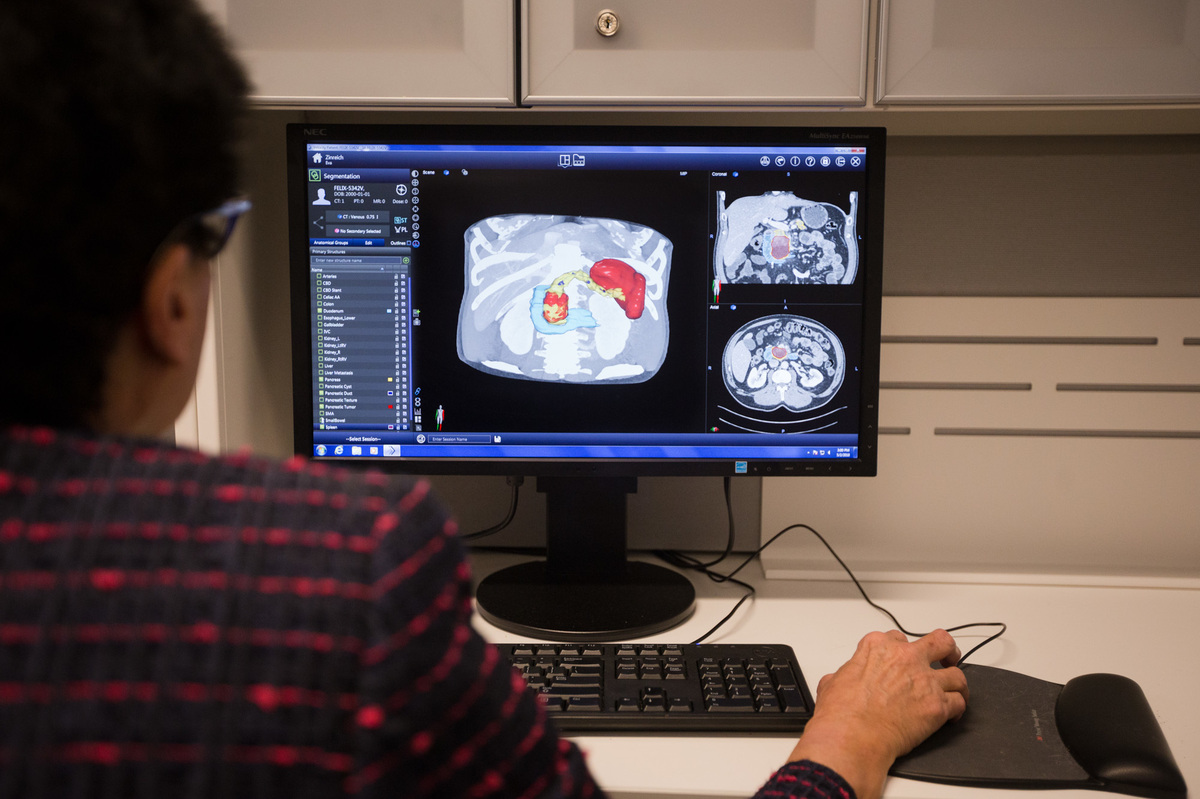

Scientists are training a computer to detect pancreatic tumors from CT scans at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, Md. The project uses anonymized patient CT scans to build a system that can recognize tumors.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

Scientists are training a computer to detect pancreatic tumors from CT scans at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, Md. The project uses anonymized patient CT scans to build a system that can recognize tumors.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

The most famous case of this nature involves a Maryland woman, Henrietta Lacks. Back in 1951, doctors at the Johns Hopkins hospital in Baltimore collected cells from her cervical cancer and turned them into the world’s first immortal cell line, which grows perpetually in the lab and is used widely in research. As documented in Rebecca Skloot’s book and an HBO biopic starring Oprah Winfrey, the family learned only much later what had transpired and received no compensation. In 2013, the National Institutes of Health came to an agreement with her family guiding the use of her genetic information, but the family has continued to raise the issue.

While those fights were about living tissue, “in a certain sense whether it’s cells or [digital] bits and bytes, it’s all information about an individual, at some level,” says Dr. Nabile Safdar, a radiologist at Emory University and author of a recent paper discussing the issue of patients’ rights as it pertains to their medical scans.

This information is increasingly being used in research, and that in turn can easily end up being used to develop a commercial product that’s worth millions. Are the patients entitled to a cut?

“That’s a question that I think we need to figure out,” Safdar says. “And if were a patient and my data were used to develop something that was being shared outside as a product, I’d want to know.”

That’s not how it’s usually done. At many research hospitals, patients routinely sign a paper, in that huge stack of admission paperwork, giving permission for the institution to use their personal data for research.

“For someone to sign away the rights in perpetuity for their data to be used for all possible research applications in the future, that’s something I think would deserve a lot of scrutiny, and that’s not something I would agree with,” Safdar says.

Here’s a current example. Researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine are mining years of CT scans that were performed initially to care for patients. Those patients signed a form saying it was okay to use that data for research. And the research has been approved by the university’s institutional review board, which is charged with weighing the ethics of research projects, says Dr. Karen Horton, director of radiology.

Horton is now using some of this data to teach computers how to recognize pancreatic cancer. She says part of their agreement is that the data are stripped of all information that could identify an individual patient, “so there’s no [privacy] risk to a patient to have their images used to train the computer.”

And Horton says technically, the data don’t belong to the patients. “Right now as the law defines it, your medical images are property of the health system,” she says. “You don’t own the image.”

But Wolf, the law professor and ethicist at Georgia State, says she’s not sure that’s a strong argument. “Yes, they [the doctors] created the scans,” she says, “but certainly the patient has rights related to the scans,” such as the right to view them and of course to decide at the outset whether they can be used in research.

It generally takes thousands of scans from many individuals to develop a commercial product, so no single person’s data is especially valuable on its own. Overall, Wolf says, patients don’t have much of a legal argument here, but there is an ethical issue.

“My own concern is not that it is problematic per se,” she says. But, “I don’t think we’ve done a really good job of letting people know that this is in fact what we do with their data.”

She cites lawsuits where blood samples that had been taken at birth ended up being used for research.

“One of the moms in the case said if ‘I had been asked I think I would have said yes,’ but it was the sense of not even being asked, and having the data used,” Wolf says. “People generally will agree, but they want to be asked, at least at some level.”

And Safdar says there are times when people might, indeed, want to object to how their data are being used.

“There’s a wealth of information in a CT scan or an MRI,” Safdar says. Looking at features such as liver fat, artery clogs and brain atrophy, researchers might calculate a probability for how long that person is likely to live.

These algorithms are generally called “black boxes,” because there’s no way to know how they reach their conclusions. And if the computer algorithm “spits out that you have two months to live, there are implications for employment, for insurability, for all kinds of things that impacts that person’s daily life,” Safdar says. “That worries me a little bit, especially when it’s not clear how that black box is making those decisions.”

And what if the algorithm has actually baked in an unconscious prejudice of some sort, he asks, such as about race, age or sex?

“When that same model, when trained [to work] on a specific group of people, is now applied to a totally different group of people, it could make totally erroneous decisions.”

These issues are becoming more pressing as these AI-based products start coming to market.

You can contact Richard Harris at rharris@npr.org.