How face recognition tech is helping the police catch criminals

Main image: Amazon's Rekognition face ID system. Credit: Amazon

“You see it in movies all the time, they zoom in on a picture and it’s all pixelated and they say ‘enhance’, and you get this nice image,” says Tom Heseltine, CEO of facial recognition software firm Aurora. “That’s not real. But with deep learning they’re trying to do that, and it’s becoming quite good. [Some facial recognition systems] are able to take that image and construct a high-resolution face.”

It sounds like something straight out of a police procedural, but thanks to improvements in facial recognition tech, real law enforcement officers have begun experimenting with it. In the UK, both London's Metropolitan Police and South Wales Police have used facial recognition systems to pick would-be troublemakers out of a crowd in real-time at large events, and at the 2017 Champions League soccer final in the Welsh capital Cardiff, police made an arrest after the system threw up a match with a database of wanted criminals.

Critics, however, claim the system is inaccurate, and South Wales Police statistics showed that 92% of nearly 2,500 matches at the Champions League final were 'false positives'. But others say that number is meaningless on its own and should only be considered in the context of how the system works. So, how does the tech work? And why, if it’s so advanced, would the number of false positives be so high?

Deep learning

The most advanced systems, Heseltine tells TechRadar, work though deep learning, a type of machine learning that uses virtual neural networks to essentially reconstruct a simulation of a human brain. You can teach the system to recognize faces by showing it hundreds of thousands of pairs of faces and telling it whether they match or not.

“You teach it by saying ‘these two are the same people, these two are different people’,” Heseltine says. “You do this on big powerful servers, typically equipped with GPUs to accelerate that learning process. It slowly learns over time, and once it’s complete you have a neural network that’s able to recognize faces.”

Aurora’s face recognition systems are used by airports, construction companies, and in other venues where security is a key consideration. Credit: Aurora

That learning process can take several days, or it could be as little as a few hours for a less advanced system. It all depends on what you want the system to do in practice. If you wanted it to recognize passport photos, then you’d just show it those types of images, which are high-quality, color photos of people facing directly at the camera.

But “if that’s all the neural network has ever seen, that’s all it’s ever going to be good at,” adds Heseltine – so you couldn’t then use that system to recognize faces in grainy CCTV footage, for example. But you can train systems to recognize lower-quality images taken from a variety of angles.

A facial recognition system can’t tell you whether two images of a face are of the same person; it simply assigns a likeness score based on the similarity in their characteristics. For example, for a camera capturing real-time video, the system could look at a face in a frame of the footage and compare it to all the faces on a known police database. It would then assign a likeness score for each face, generating a long list of numbers. It still relies on a human to confirm whether two faces are matched.

A police van equipped with a facial recognition camera. Credit: South Wales Police

The likeness score threshold above which you verify a potential match varies considerably, Heseltine explains, depending on the importance of finding a match, the consequences for a false positive, and the man power available. For example, if the police were looking to catch a petty criminal, they might only look at the very highest likeness scores. But if they were trying to catch a serial killer they might set the threshold lower, and follow up anybody that the system identifies as a potential match, given the heightened importance of catching that person.

The 'likeness threshold'

The best systems are now very accurate, Heseltine says, and will nearly always give high likeness scores to matching faces if the image quality is good enough. So, why would police systems have high false positives? There are several factors at play. Firstly, the percentage of false positives, when taken in isolation, is “almost meaningless” because it simply reflects the 'likeness threshold' that the police chose to record a potential match. They could have set the threshold very high, and had no false positives, but it would also mean the system wouldn’t work for catching criminals.

“If they’re making 200 false IDs, that’s because they set the threshold such that it would make 200 false IDs. Maybe that 200 number is because that’s a manageable figure that a human can review and decide what to do about it.

“They could make that 0 and have a fantastic report if they turned [the threshold] up a notch. But I imagine from the police perspective, if you’re trying to find a serial rapist you’d rather look through 200 matches and find out if they’re in there.”

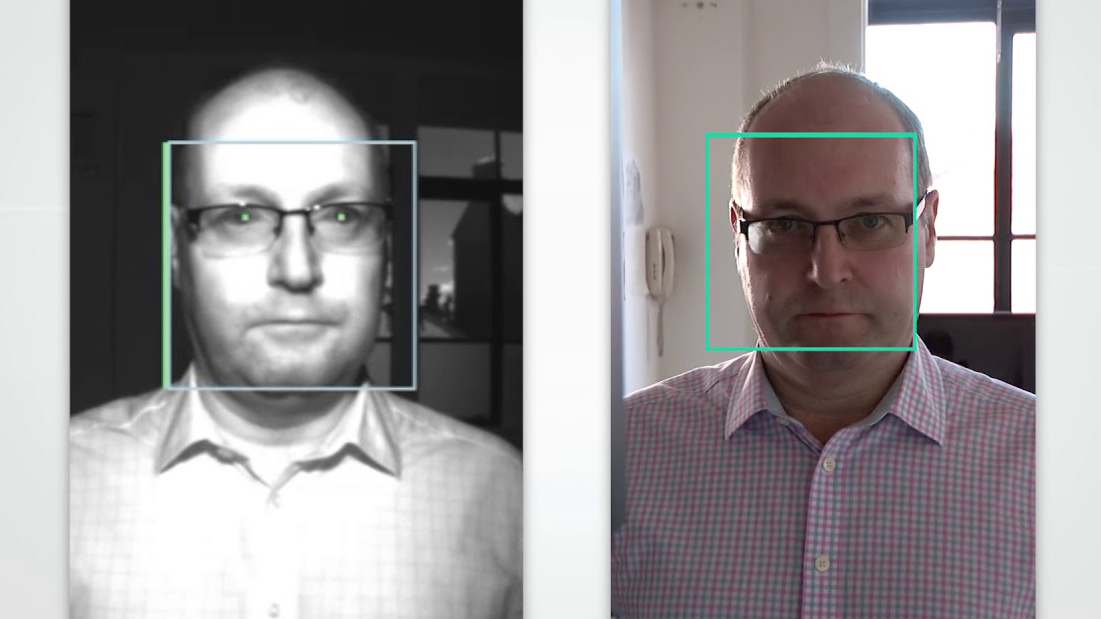

Aurora’s face recognition systems use specially designed near-IR sensors to ensure reliability in all lighting conditions. Credit: Aurora

It’s a similar situation in airports, where Aurora’s technology is primarily deployed. Images of passengers’ faces are captured when they enter a secure area, and that image is referenced when that same person tries to board a plane.

A low likeness score could indicate that somebody else has taken the passenger’s place, and some false positives are necessary to ensure real cases are caught. Airports will set the threshold based on the number of passengers they can follow up. “We can afford to stop and question and search one in 100 passengers, that’s what we can deal with, so that’s what they set it at,” Heseltine explains.

You can also get high false positives because of a large database to match against, a high volume of images – either due to lots of cameras or footage with a high frame rate – or if you run the system over a long period. But weaknesses in the technology are also partly to blame.

Facial recognition software works very well on clearly lit, high-quality images, but it can struggle when the image quality is poor. Aurora’s systems in airports use cameras specifically designed for that purpose, but other cameras, such as in CCTV systems, “have been installed without facial recognition in mind, and they’re probably five, 10 years old”, Heseltine says.

Concerns about the South Wales Police trial are addressed in the above video by deputy chief constable Richard Lewis, who says that some of the images it used weren’t of sufficient quality, and so officers were identifying people wrongly because they weren’t able to get the detail of a picture. The force has since installed special cameras on vans that work better.

It can also be difficult for a system to identify people if their head is at an angle, or if part of their face is obscured by shadow. And ultimately, it’s “extremely easy” to avoid being recognized by the cameras if you “cover your face with a baseball cap, dark glasses, and a shirt or jumper that comes up high,” Heseltine says.

“We can afford to stop and question and search one in 100 passengers, so that’s what they set the threshold at,”

Tom Heseltine, CEO, Aurora

In a public space, you can’t do much about that, but facial recognition providers are working to improve detection in poor quality images, or where part of the face is obscured. In addition to the CSI-style zoom-and-enhance technique, other innovations include systems that can predict what the left side of the face looks like if it can only see the right side, as well as ones that, Hesletine says “regenerate an area covered by shadow”.

Privacy concerns related to the way police and other organizations use photos and other data linked to the systems will remain, and this week workers at Amazon demanded that the company stop selling its facial recognition software, called Rekognition, to law enforcement. But improvements in the accuracy of the tech, and a reduction in false positives, might help to assuage the concerns of some critics.

The evaluation of the year-long trial of the use of the technology by South Wales Police is still ongoing, and the results could prove pivotal to the future use of facial recognition in the UK.

South Wales Police and the National Police Chiefs' Council declined to be interviewed for this article.

TechRadar's Next Up series is brought to you in association with Honor